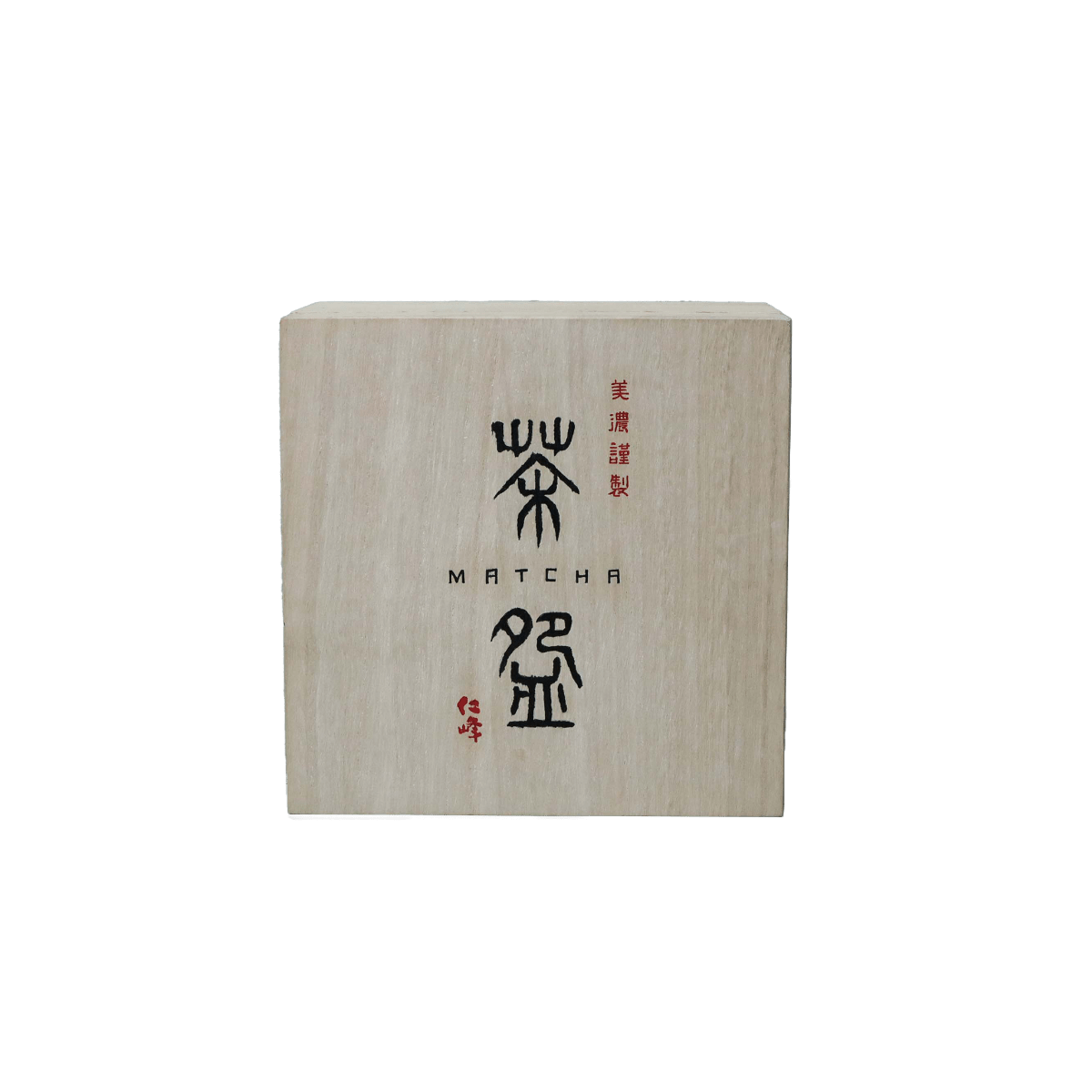

Mino ware (美濃焼, Minoyaki) refers to a diverse group of ceramics produced primarily in Gifu Prefecture’s Tōnō region, encompassing the towns of Tajimi, Toki, Mizunami, and Kani.

With over 1,300 years of continuous history and the largest production output among all Japanese pottery types, Mino ware is both a cornerstone of traditional Japanese aesthetics and a vibrant part of contemporary tableware culture.

At a Glance: Fast Facts About Mino Ware

- Location: Mino ware originates in the heart of Japan, within Gifu Prefecture's Tōnō region, made up of the towns of Tajimi, Toki, Mizunami, and Kani. The area is famed for its rich clay deposits and centuries-old ceramic tradition.

- Historical Roots: Mino ware traces its origins to the 5th century, with Sueki pottery, and reached artistic maturity during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1600). Influenced by warlord Oda Nobunaga and tea master Sen no Rikyū, artisans like Furuta Oribe led a renaissance in Japanese ceramic design. The region continued to evolve through the Edo period, and industrialization during the Meiji and Showa eras cemented Mino ware’s place in both local use and global export markets.

-

Variety of Styles: Mino ware encompasses over 15 officially recognized styles, making it the most stylistically diverse ceramic tradition in Japan. Notable styles include:

- Shino: Thick glaze with rustic textures and iron-oxide brushwork, often featuring motifs like autumn grasses.

- Oribe: Bold green copper glaze and abstract, asymmetrical forms.

- Kizeto: A warm, yellow-glazed ware valued for its understated beauty and simplicity.

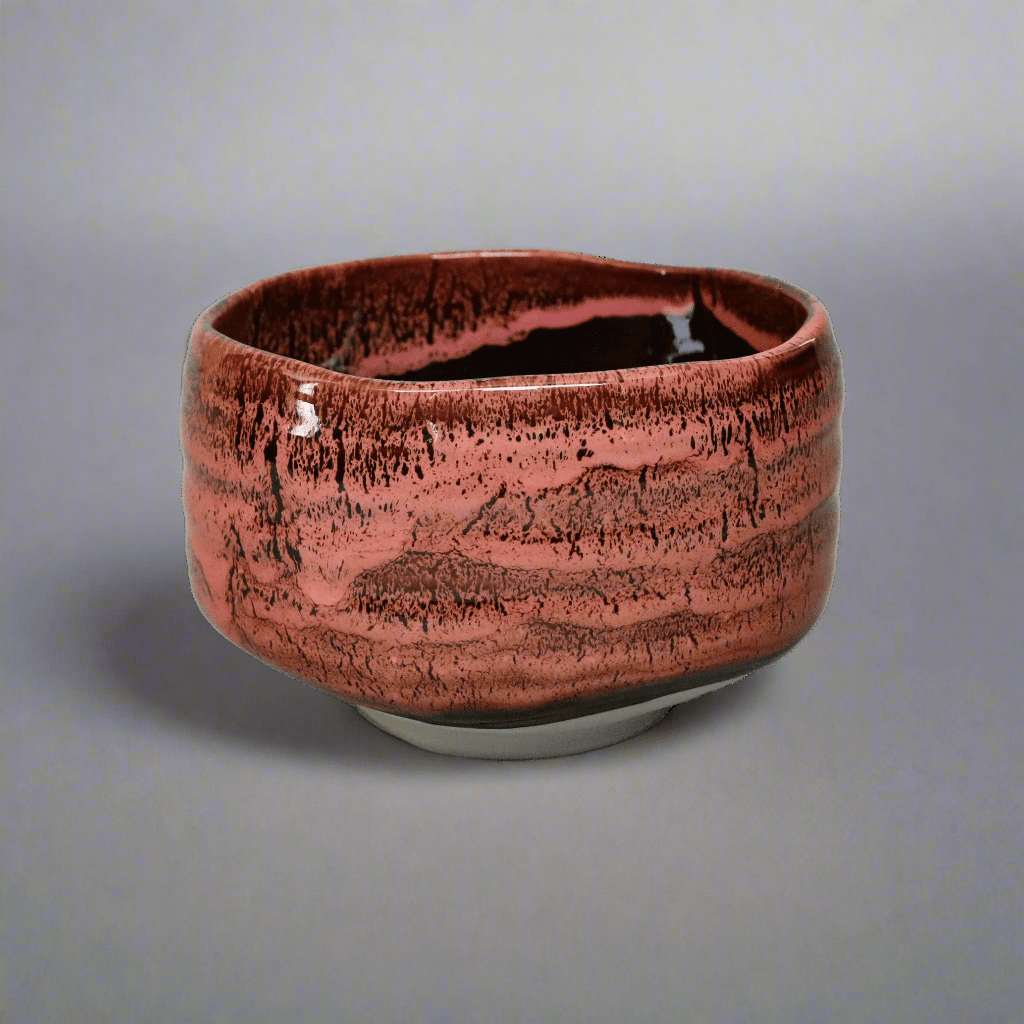

- Setoguro: Deep, glossy black glaze produced by rapid cooling, dramatic and favored for tea bowls.

- Other styles include Haishino, Ofukei, Aka-e, and Shirotenmoku, reflecting continued artistic experimentation.

- Production Volume: Mino ware accounts for over 50% (by some estimates up to 60%) of all ceramic production in Japan, making it the country's most prolific and accessible pottery style.

- Everyday Relevance: Mino ware is part of daily life in Japan. It’s widely used for donburi rice bowls, tea cups, sake bottles, vases, and incense holders. You'll find Mino ware in homes, restaurants, cafés, and traditional inns. Its blend of beauty and practicality makes it ideal for both casual and formal dining.

-

Craftsmanship and Techniques: Production typically includes:

- Clay preparation from mineral-rich deposits in Gifu.

- Shaping through potter’s wheel molding or hand-building methods.

- Trimming and drying to ensure structural precision.

- Glazing with feldspar, ash, and iron-based mixtures.

- Firing in traditional anagama or noborigama kilns, or modern gas/electric kilns.

- Finishing by hand, with attention to balance, glaze variation, and form.

- Modern Adaptation & Innovation: Mino ware continues to evolve. New glaze formulas and minimalist forms cater to modern aesthetics. Young artists reinterpret traditional styles for global audiences. International workshops and designer collaborations are reviving interest.

- Challenges and Revitalization: Mino ware faces a shrinking artisan base and limited natural clay resources, as well as pressure from low-cost global ceramics. In response, communities support revitalization through craft fairs, artist residencies, design education, and government-backed cultural tourism initiatives.

History and Origins: From Sueki to the Tea Ceremony

The roots of Mino ware trace back to the Heian period (794–1185), when potters migrated from neighboring regions like Seto and began producing Sueki—unglazed, high-fired earthenware—in Gifu’s mountainous terrain. The Mino style flourished during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1600), a time of political upheaval and artistic innovation.

Under the patronage of Oda Nobunaga and with the aesthetic guidance of Sen no Rikyū, Mino kilns began crafting refined vessels tailored to chanoyu (tea gatherings). Innovators like Furuta Oribe, a disciple of Rikyū, introduced experimental shapes and glazes that defied the symmetry and perfection of Chinese porcelain, giving rise to some of Mino’s most iconic substyles.

Characteristics and Styles: Diversity Through Innovation

Unlike other Japanese ceramic traditions tied to a narrow aesthetic, Mino ware is celebrated for its stylistic diversity. The four Momoyama-era classics (Shino, Oribe, Kizeto, and Setoguro) remain cornerstones, but over 15 styles are officially recognized today.

Together these styles reflect Mino’s unique ability to accommodate both contemporary tastes and traditional sensibilities which is a rare trait in the world of Japanese ceramics.

The Production Process: From Clay to Masterpiece

Mino ware production begins with the high-quality clay found in Gifu's Tōnō region. Potters use both potter’s wheel molding and hand-building techniques depending on the form.

Key steps include:

- Clay preparation using sediment-rich, iron-bearing earth.

- Shaping with wheels or hand techniques.

- Drying and trimming to ensure structural precision.

- Glazing, often using feldspar, iron slip, or natural ash.

- Firing in traditional wood-fired kilns or modern gas kilns.

- Finishing touches, including inspection and polishing.

Every piece, whether artisan-made or mass-produced, embodies a balance of technical mastery and artistic intention.

Notable Artists and Cultural Figures

Mino ware’s identity has been shaped by countless artisans over centuries, but none more so than Furuta Oribe, whose playful, deconstructed forms remain influential today. In the modern era, young potters and ceramicists continue to push boundaries, exhibiting work in museums, biennales, and local galleries throughout Japan and abroad.

Their work bridges ancient forms with global tastes, ensuring that Mino ware remains at the forefront of contemporary ceramic expression.

Conclusion: Why Mino Ware Matters

More than just pottery, Mino ware represents the enduring beauty of Japanese craftsmanship, adaptive, expressive, and rooted in nature. Whether in the quiet wabi-sabi of a Shino teabowl or the bold flair of an Oribe plate, Mino ceramics invite us to pause, appreciate, and connect with tradition through everyday life.

Share: