Introduction: A Little Paper with Big Meaning

If you’ve ever visited a Japanese shrine (jinja) or temple (tera), you may have noticed people holding small folded slips of paper, sometimes tying them to racks, strings, or tree branches. These are omikuji (おみくじ, “sacred lottery fortunes”) a tradition that blends spirituality, self-reflection, and everyday hope. Whether predicting “super great luck” (dai-kichi) or warning of “great misfortune” (dai-kyō), omikuji fascinate locals and visitors alike.

This guide explains what omikuji are, their history, how to draw and interpret them, and the customs around keeping or tying them, plus how they’re adapting for today’s international audience.

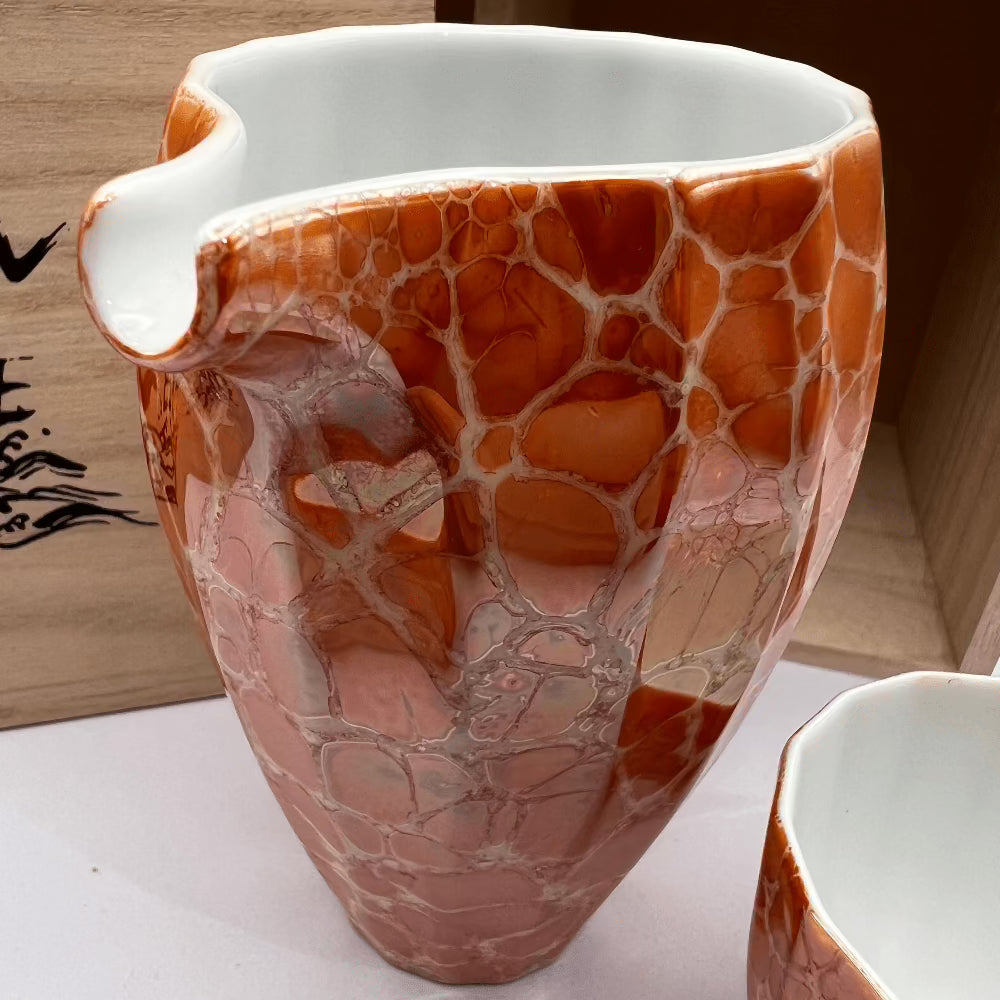

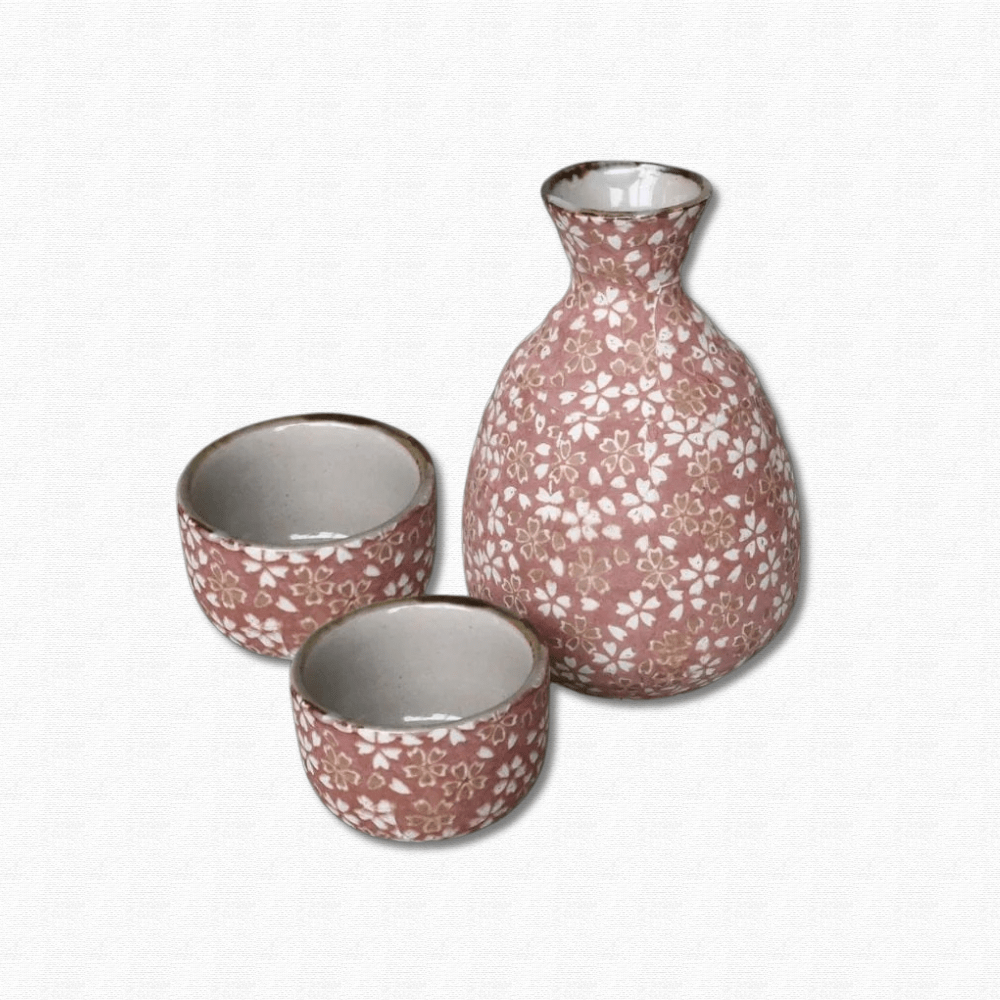

After writing your omikuji share a cup of sake with friends to continue the good spirits!

What is Omikuji and Its Origins

The word omikuji combines the honorific o and mikuji (lot/drawing). The practice traces to ancient China and the use of drawing lots for guidance. During the Heian period (794–1185), Japanese aristocrats and religious leaders sought divine advice for political and personal decisions, reflecting a deep belief in the gods (kami). Samurai also consulted omikuji for direction in critical moments.

Over time, omikuji evolved from elite ritual to everyday practice. Today it’s a popular annual event at hatsumōde (初詣, the first shrine visit of the year), and many people draw omikuji anytime they seek guidance or a moment of self-reflection, a hallmark of Japanese culture.

How to Draw and Read Omikuji

The Process at Shrines and Temples

- Cylinder box (mikuji-bo): Shake the cylinder until a numbered stick drops out. Match the number to a drawer on the omikuji box to receive your fortune slip (fortune-telling paper strip).

- Square pillar box: A tall wooden container with a similar draw-by-number process.

- Karakuri omikuji: Mechanical or playful delivery, sometimes by a mascot of a cat, a mascot of a pigeon, or even a whimsical robot lion.

- Vending machines: Common at larger or tourist-friendly grounds.

There is usually a small fee (often 100–300 yen). You’ll also find explanatory signage; many places provide a brief explanation in simple Japanese or multiple languages.

Reading the Fortune Slip

Your paper begins with an overall fortune level, followed by concise advice in themed sections. Increasingly, sites offer english omikuji, clear english translation, or fully multilingual omikuji. Some preserve the classical poem form, occasionally drawing from Chinese poems or modern Japanese, while others present straightforward interpretation notes for visitors.

Types and Meanings of Omikuji Fortunes

- 大吉 (dai-kichi) — super great luck

- 中吉 (chū-kichi) — middle luck

- 小吉 (shō-kichi) — small luck

- 半吉 (han-kichi) — half luck

- 末吉 (sue-kichi) — future luck (luck will come later)

- 吉 (kichi) — luck

- 凶 (kyō) — misfortune

- 小凶 (shō-kyō) — small misfortune

- 半凶 (han-kyō) — half misfortune

- 末凶 (sue-kyō) — future misfortune

- 大凶 (dai-kyō) — great misfortune

These levels set the tone, but the real value lies in the detailed guidance that follows.

Interpreting Specific Omikuji Sections

- 願事 (negaigoto) — personal wishes

- 学問 (gakumon) — studies and learning

- 仕事 / 商売 (shigoto / shōbai) — work / business success

- 恋愛 / 縁談 (ren’ai / en-dan) — love / marriage

- 旅行 (ryokō) — travel

- 健康 (kenkō) — health

- 失物 (usemono) — lost belongings

Wording may be poetic, metaphorical, or brief, encouraging thoughtful interpretation. A line like “wait for the wind to shift” suggests patience before taking action.

Frequently Asked Questions and Customs

When do people draw omikuji?

The most popular time is New Year’s visits (hatsumōde), but many draw omikuji before exams, weddings, business launches, or travel, any moment when a little guidance helps.

What if I get bad luck?

Don’t worry, omikuji aren’t final judgments. The common custom is to tie the slip at a designated spot (racks, strings, or branches) within the grounds. You’ll often see fluttering rows of “hanging omikuji”, symbolically leaving misfortune behind. Good fortunes can be tied (to “secure” the blessing) or kept as a lucky charm in your wallet or a small wooden box at home.

Why mascots, machines, and robots?

Many sites use mascot omikuji (like a cat or pigeon) to welcome families and newcomers. Others feature vending machines or playful karakuri like a robot lion, showing how tradition and modern creativity meet in Japan.

What to Do After Receiving Omikuji

- Good fortune (dai-kichi, kichi, etc.): Keep it close wallet, bag, or desk as a reminder of blessings.

- Bad fortune (kyō, dai-kyō): Tie it at the shrine/temple’s designated spot (racks, strings, or trees) the classic scene of shimmering, hanging omikuji.

Ultimately, omikuji emphasize reflection, encouragement, and practical advice rather than fixed fate.

Bringing the Experience Home

While omikuji are best experienced in Japan, the ritual pausing to reflect on your negaigoto (wishes) fits beautifully into everyday life. Pair a quiet moment with a bowl of warm tea: sipping from authentic Japanese handcrafted tableware (a favorite cup, a matcha set, or a small ceramic bowl) turns a simple pause into a meaningful practice connecting tradition and modern living.

Conclusion: A Fortune Beyond Paper

Omikuji remind us that life swings between luck and challenge, and that guidance often arrives in modest forms. On your next visit to a shrine or temple, draw a slip not just to peek at the future but to connect with a centuries-old tradition of hope, humility, and reflection. Whether you tie your paper on site or carry it home, the feeling lingers much like enjoying tea from a beautifully crafted Japanese cup. Small rituals, big meaning.

Share: