Among Japan’s most celebrated traditional crafts, lacquerware known as urushi serves as a testament to centuries of artistic ingenuity and spiritual reverence. Valued both for its striking beauty and unparalleled durability, Japanese lacquerware blends function and artistry into objects cherished across generations.

History and Evolution

Japanese lacquerware can be traced back to the Jōmon era (around 14,000–300 BCE), when artisans first experimented with coating pottery in natural urushi sap. Over the centuries, the craft developed significantly, gaining prominence during the Heian (794–1185) and Kamakura (1185–1333) periods, where it was closely tied to religious practices and the refined tastes of the imperial court.

By the time of the Edo period (1603–1868), lacquerware had evolved into both a symbol of prestige for the elite and a functional element in the daily lives of commoners. While Chinese Song Dynasty artistry inspired and shaped certain techniques, Japan gradually cultivated its own distinct aesthetic. One notable example is Negoro-nuri, a style where layers of red lacquer subtly emerge through a black topcoat.

During the Meiji era (1868–1912), the craft gained worldwide recognition. Exhibited at international fairs, Japanese lacquerware fascinated foreign audiences and became a celebrated cultural export, showcasing the nation’s artistic heritage to the world.

Techniques and Crafting Process

Lacquerware production begins with the collection of sap from the urushi tree (Toxicodendron vernicifluum), which grows naturally across East Asia. From each mature tree, artisans can harvest less than a single cup (roughly 200 milliliters) over the course of an entire season. Once taken, the tree is usually felled, making the resource extremely valuable and costly. Japanese-sourced urushi is especially valued for its exceptional clarity and durable finish, yet declining domestic supply has led to significant reliance on imports, mainly from China.

However before use, the raw resin must undergo meticulous filtering and refining. It is then applied with precision to wooden or composite cores in ultra-thin layers, each carefully cured in a humid environment so the coating can polymerize properly. A masterpiece may involve more than thirty individual coats, with each layer sanded smooth and polished before the next is added. If the lacquer is spread too thickly, the exterior can harden while the inner layers remain soft, potentially ruining months of work. Completing a single refined piece often requires not just weeks, but several months sometimes even years.

Among the time-honored techniques are:

-

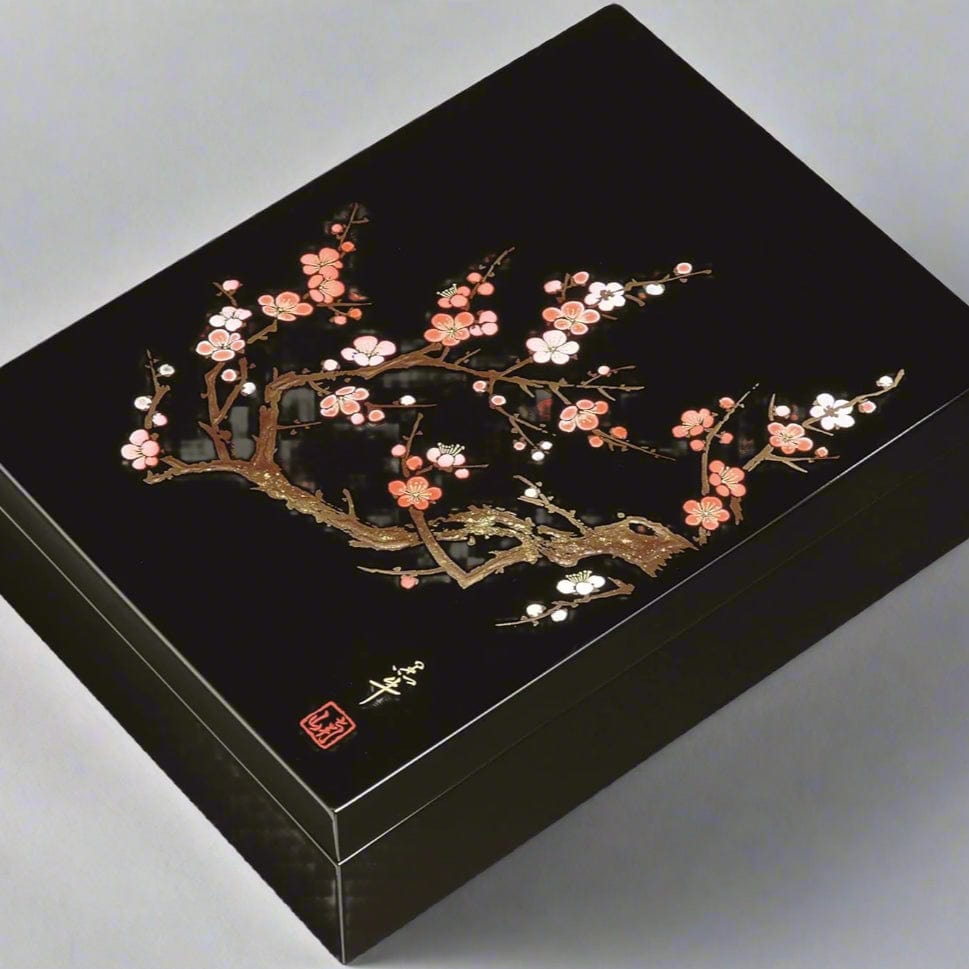

Maki-e – Perhaps the most recognized decorative style, intricate motifs are drawn with wet lacquer and then dusted with gold or silver powders. The shimmering particles become sealed beneath additional coats, resulting in delicate, luminous patterns that frequently depict flowers, seasonal scenes, or mythical beings with symbolic meaning.

-

Chinkin – This engraving approach involves carving fine lines into the cured lacquer surface using sharp chisels. Gold leaf or powder is then pressed into the grooves, creating a contrast with the vivid sparkle of maki-e.

-

Raden – A technique of inlaying wafer-thin pieces of mother-of-pearl or abalone shell. The embedded fragments glimmer with iridescence,enhancing floral or geometric compositions.

-

Usubiki – A minimalist style that uses ultra-light layers of lacquer so sheer that the natural grain of the wood subtly remains visible. This approach highlights the beauty of the material beneath.

-

Hiki – Practiced in regions like Yamanaka, this method employs a lathe to spin the wooden core while lacquer is brushed on. It produces uniform coatings with subtle concentric textures.

Each of these methods demands years of dedicated training. The results are not just functional objects but reflections of patience, skill, and artistic devotion.

Regional Variations and Distinctive Styles

Across Japan, lacquerware has evolved into regionally distinct traditions, each with its own hallmark techniques and visual identity:

-

Wajima-nuri (Ishikawa Prefecture)

Renowned for its strength and refined ornamentation, Wajima-nuri incorporates a special base layer mixed with jinoko (a fine diatomaceous earth) that adds to the durability. Decorative finishes often employ chinkin engraving or maki-e gilding. Artisans typically devote years of practice just to perfect the intricate undercoating process before moving on to surface decoration. -

Tsugaru-nuri (Aomori Prefecture)

This northern style is famous for its karanuri technique, involving alternating dozens of colored lacquer coats (sometimes as many as forty-eight layers). After extensive polishing, these layers reveal a distinctive mottled pattern reminiscent of raindrops. The timeline for each piece can span months. -

Yamanaka Lacquerware (Ishikawa Prefecture)

Highly regarded for precision, Yamanaka wares are shaped on a lathe to create countless fine ridges that give the surface a unique tactile quality. The level of detail achieved in this style is considered unparalleled among lacquer traditions worldwide. -

Echizen Lacquerware (Fukui Prefecture)

Known for balancing elegance with everyday practicality, Echizen lacquerware embraces both opaque and semi-transparent finishes and is celebrated for maintaining artisanal quality while remaining relatively affordable. -

Kanazawa Lacquerware

Influenced by the refined aesthetics of aristocratic culture, this style is distinguished by lavish gold maki-e motifs often inspired by seasonal poems, classical literature and traditional courtly themes. -

Hida Shunkei (Gifu Prefecture)

In contrast to heavily decorative styles, Shunkei ware highlights the natural beauty of wood by coating it with a clear amber-toned lacquer. This organic approach makes it especially popular for trays and lidded tea ceremony container

Applications and Uses

Beyond aesthetics, lacquerware serves a multitude of purposes in Japanese life. Commonly used items include:

-

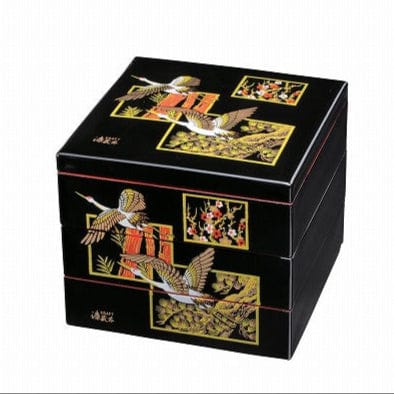

Tableware: Lacquered bowls, trays, plates, and jubako boxes are central to Japanese dining culture. The material's insulating properties help maintain food temperature and its smooth surface makes it ideal for delicate cuisine. Sake cups, often adorned with auspicious motifs.

-

Ceremonial Objects: Urushi is integral to religious life in Japan. Buddhist altars (butsudan), ritual implements, and entire shrine interiors are often coated in black or red lacquer to signify purity and sanctity. Temples such as Kinkaku-ji contain elements finished with lacquer and gold leaf.

-

Decorative Art: Lacquerware items like writing boxes (suzuri-bako), incense containers, and combs were historically treasured by nobles and samurai families. These pieces often feature complex maki-e and raden.

-

Functional Craft: Historically, lacquer was applied to samurai armor, scabbards, and furnishings to protect them from moisture and insect damage. Some experimental uses included coating sections of early automobile bodies and fountain pens. Its water-resistant properties made it an early natural plastic.

Artisans and Notable Figures

Japan has honored many lacquer artists as Living National Treasures including Kazumi Murose, a preeminent maki-e master. Historical innovators like Shibata Zeshin (1830–1891) revolutionized lacquer painting by combining Western realism with traditional technique while Nakayama Komin contributed significantly to the modernization of Edo-period lacquer art. Contemporary artisans like Unryuan Kitamura Tatsuo carry the craft forward with museum-grade pieces.

Other noteworthy traditions include:

-

Kawatsura Shikki (Akita Prefecture): This style emphasizes thick, hard finishes applied with careful layering. The surface is polished to a soft gloss.

-

Wakasa Lacquerware (Fukui Prefecture): Distinguished by embedded colored layers that are sanded and polished to reveal marble-like patterns. Wakasa pieces are particularly common in chopsticks and tea ceremony utensils.

Cultural Significance and Recognition

Lacquerware holds a vital place in Japan’s cultural heritage. Recognized as an Important Intangible Cultural Property, the craft embodies traditional aesthetics and spiritual values particularly impermanence (mujō) and reverence for nature. It also figures prominently in Shinto rituals and seasonal observances.

Japanese lacquerware gained acclaim at World Fairs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, becoming an emblem of national pride and a powerful symbol in the global art export market. Its influence extended into Art Nouveau and modern European design.

Collections and Preservation

Exquisite lacquerware is preserved in top institutions such as the Tokyo National Museum, the Tokugawa Art Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Among Japan’s most treasured pieces is the 12th-century Tebako (Cosmetic Box) adorned with maki-e and raden and designated a National Treasure. Another example is the Toiletry Case with Cart Wheels in Stream motif, showcasing Heian-period elegance.

Preservation requires diligence: urushi is sensitive to ultraviolet light and extreme temperature changes. With proper care, however, it does not degrade rather, it ages gracefully, developing a lustrous patina that adds character over time.

Modern Challenges and Industry Trends

Despite its revered status, Japan’s lacquerware industry faces modern challenges. Domestic production of urushi has dwindled, with over 95% of lacquer now imported from China. Young artisans are few, as the years-long training and limited financial reward discourage new entrants.

Yet efforts are underway to revive the craft. Educational programs, government subsidies, and design collaborations with contemporary artists and architects are helping reposition lacquerware for modern living.

Conclusion

Japanese lacquerware is a decorative craft. Whether admired in a museum or used during a tea ceremony, each piece tells a story of patience, precision, and timeless beauty. As Japan works to revitalize its traditional industries, lacquerware continues to inspire offering an enduring link between the past and present.

Share: