Sake cups are far more than simple drinking vessels. In Japanese culture, they carry deep meaning, reflecting centuries of craftsmanship, social custom, and regional artistry. Whether used in formal ceremonies or casual gatherings, sake cups speak volumes through their form, material, and role in etiquette.

They are vessels not only for sake but for communication, tradition, and aesthetic philosophy.

The Art of Materials and Craftsmanship

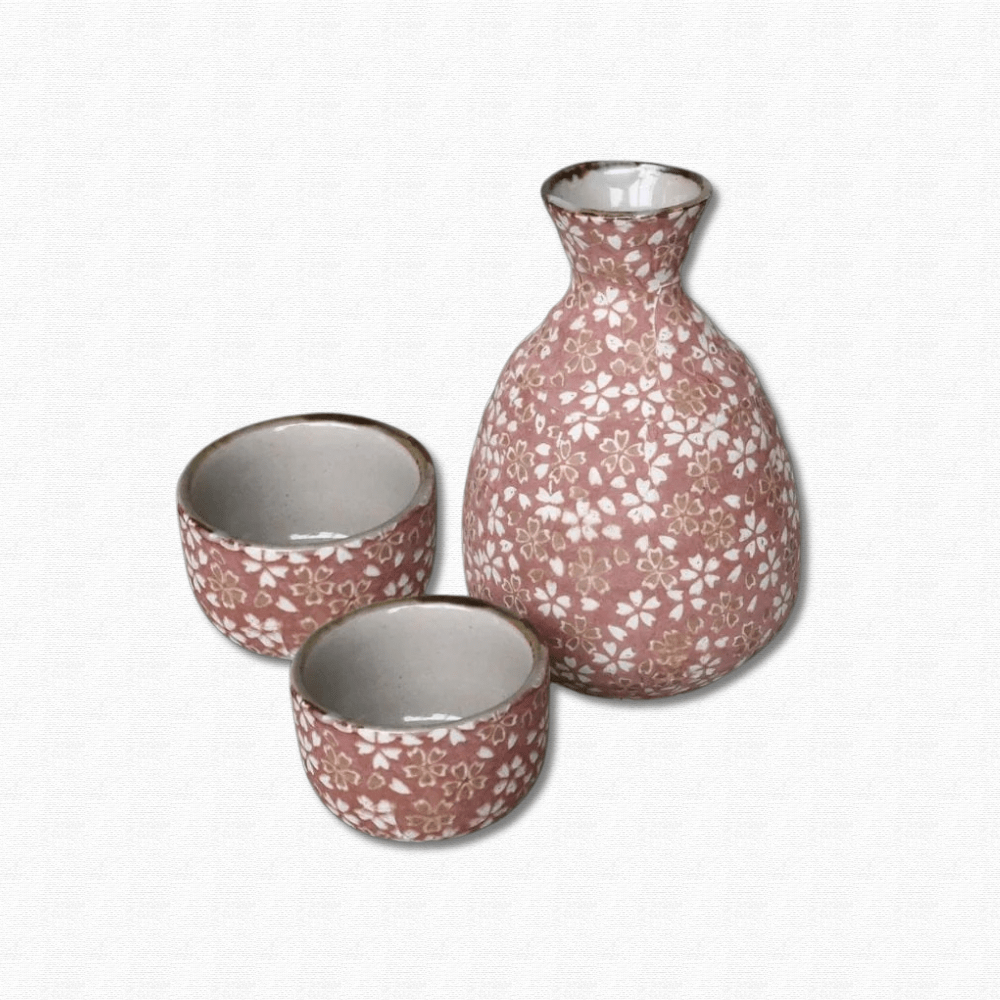

Sake cups are made from a range of materials, each chosen to elevate the drinking experience. Ceramic is the most common, offering warmth and a tactile connection to the earth. Styles like Bizen-yaki, Shigaraki-yaki, and Hagi-yaki showcase regional variation in clay texture, firing methods, and glaze. Porcelain cups, often thinner and more refined, offer a smoother surface and are favored for their elegance.

Glass sake cups, including Edo Kiriko with its brilliant cuts and reflections, highlight the clarity and color of chilled sake. Wooden cups, especially hinoki (Japanese cypress) masu, bring a fragrant, rustic charm to ceremonial settings. Lacquered wood, gold, and silver are often reserved for festive occasions, highlighting the status or intent of the gathering. Even modern materials like temperature-sensitive ceramics and clear stemware reflect the evolution of sake culture while maintaining reverence for form and function.

Types of Sake Cups and Their Significance

Each type of sake cup serves a different purpose and sets a particular mood. The small, rounded ochoko is used in everyday settings and promotes quick, reciprocal pours between host and guest. Guinomi, slightly larger and more robust, are preferred by those who savor sake’s aroma and flavor. Sakazuki—wide, shallow cups—are traditionally used in weddings or Shinto rituals, symbolizing purity and solemnity.

The masu, a square wooden cup originally used for measuring rice, now symbolizes prosperity and abundance. It is sometimes paired with glass cups inside for aesthetic effect or overflow pouring, an act that signals generosity. More specialized vessels like katakuchi (spouted sake servers) and chirori (metal flasks for warming sake) complete the experience, often chosen to match sake temperature, variety, or season.

Serving Etiquette and Cultural Meaning

Sake is rarely poured for oneself in Japan. Instead, it is customary to pour for others—a ritual that fosters humility, attentiveness, and connection. The type of cup used reinforces this interaction. Ochoko cups, due to their size, necessitate frequent refilling, encouraging engagement. Pouring from a tokkuri (ceramic flask) into a guest’s cup becomes a gesture of respect, care, and social harmony.

During formal events like the tea ceremony or New Year celebrations, the cup choice becomes highly symbolic. A lacquered sakazuki might be used to emphasize the spiritual purity of the occasion. Meanwhile, in intimate gatherings, a handmade guinomi might be chosen to honor the guest with something uniquely crafted and personal.

Symbolism and the Aesthetics of Sake Cups

Sake cups are not just functional—they are carriers of visual poetry. Subtle glazes, natural textures, or asymmetrical forms express wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic of impermanence and beauty in imperfection. A cup may recall a mountain stream, a misty dawn, or the bark of a tree. This aesthetic resonance enhances the sensory experience of drinking sake.

Many sake cups are given as gifts, conveying affection, appreciation, or even prayers for good fortune. The act of choosing a sake cup for someone else is deeply thoughtful—it's about honoring their taste, their personality, and the occasion. In this way, sake cups become part of memory-making, forming quiet but enduring connections between people.

Conclusion: More Than a Vessel

To hold a sake cup in one’s hand is to hold a piece of Japanese culture—one shaped by history, refined through artistry, and enriched by shared human experience. Whether rustic or refined, plain or ornate, sake cups invite us to pause, pour, and appreciate not just the drink, but the spirit of togetherness it represents.

Share: