Behind every masterpiece of Japanese ceramics lies the kiln. Known not only for its technical role in pottery making but also for its cultural and regional symbolism, the Japanese kiln has shaped Japanese pottery for over a thousand years.

From rustic wood-fired chambers nestled in mountain villages to sophisticated multi-chambered kilns built into hillsides, these furnaces are as diverse as the wares they produce.

A Brief History: Kilns as Cultural Heritage

Kilns have been at the center of Japanese ceramic production since the Kofun period (3rd–6th century) evolving alongside Japan’s rich pottery traditions. The Six Ancient Kilns (Bizen, Shigaraki, Seto, Echizen, Tamba, and Tokoname) are officially recognized as Japan Heritage sites for their historical significance and continuing legacy in ceramic craftsmanship. Each region developed a unique kiln style suited to its local clay, topography, and pottery type.

Types of Japanese Kilns: Time-Tested Technologies

1. Anagama Kiln (穴窯) – The “Cave Kiln”

A single-chamber wood-fired kiln built into a hillside. Anagama kilns produce natural ash glazes and flame markings due to prolonged wood stoking and irregular airflow.

2. Noborigama Kiln (登り窯) – The Climbing Kiln

A multi-chambered stepped kiln built on a slope. Heat rises from the bottom firebox and flows upward through connected chambers increasing the heat efficiency and volume capacity. It's ideal for large-scale pottery production in regions like Shigaraki and Tokoname.

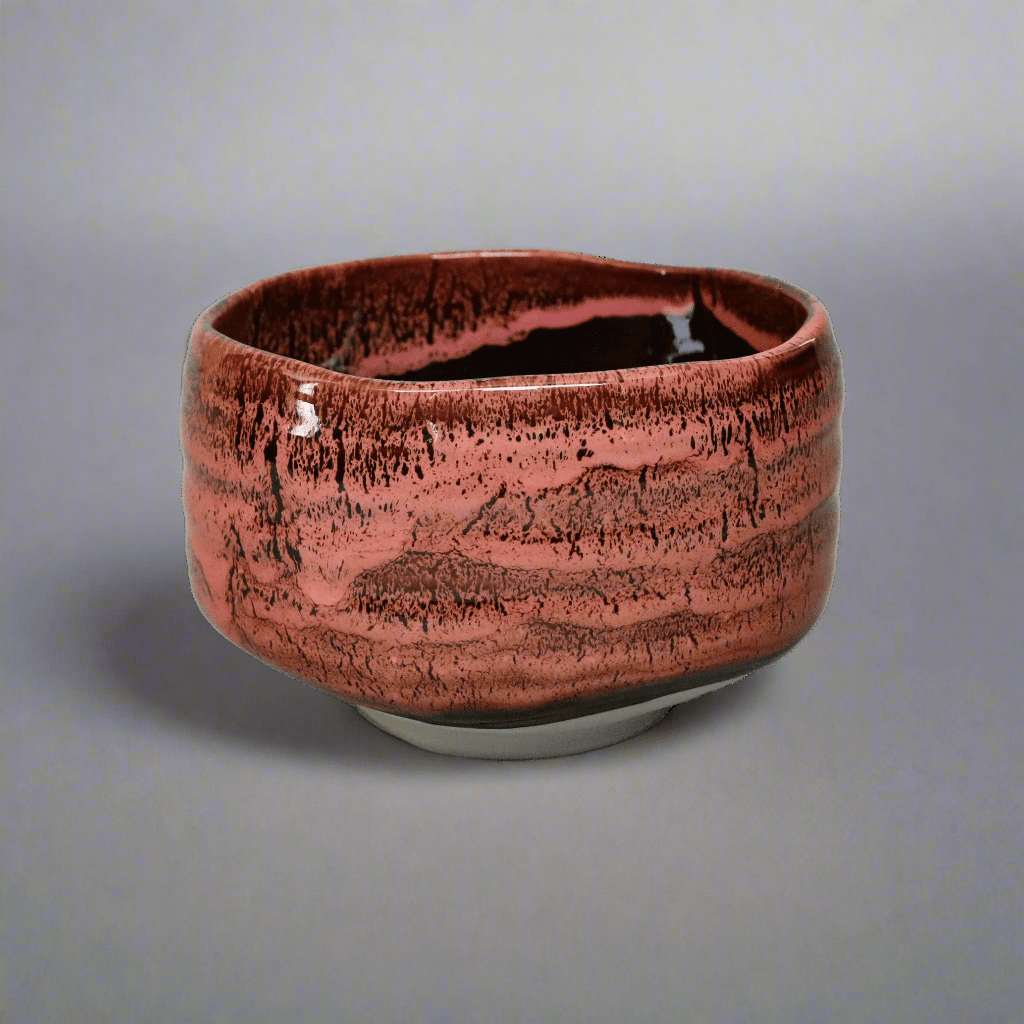

3. Raku Kiln (楽窯) – The Ceremonial Kiln

Small and rapidly fired the Raku kiln is used for hand-formed, low-fired ware. It's traditionally tied to tea ceremony culture. Pieces are removed while hot and cooled in open air or water which results in unpredictable crackles and textures.

4. Jagama / Tube Kilns (蛇窯) – The Snake Kiln

A long, serpentine kiln similar to Anagama but stretched in shape. These kilns allow for slow, gradual heat movement and are often used in rural regions to produce rustic ware.

Each kiln type contributes its own surface texture, natural glaze, and fire-induced coloration. This is especially evident in yakishime (high-fired unglazed stoneware) where kilns like Anagama or Noborigama impart ash deposits and flame patterns that no artificial glaze can replicate.

Kiln Firing Techniques: The Dance of Flame and Clay

Firing in traditional Japanese kilns is a science as well as an art. Potters must control the temperature, stoking rhythm, and oxygen flow to create specific effects.

- Stoking & Ember Immersion: Frequent wood feeding builds intense heat and causes molten fly ash to glaze the surface naturally.

- Flame Path: As fire travels through the kiln its turbulence affects each pot differently which creates gradients of color and ash accumulation.

- Fly Ash & Volatile Salts: These natural byproducts settle on ceramic surfaces and end up forming organic, glossy finishes without any added glaze.

- Counter-Flow Air Exchange: In chambered kilns the exhaust from one chamber preheats the next optimizing combustion and conserving fuel all in one.

The Evolution and Future of Japanese Kilns

While Japan's kiln legacy is steeped in tradition, today’s potters also push the boundaries of modern kiln design.

Key trends shaping the future include:

- Hybrid kilns that blend wood-firing aesthetics with gas or electric systems for better temperature control and environmental sustainability.

- Smaller-scale climbing kilns suited for urban studios that retain the soul of the noborigama but adapt to limited space and regulations.

- Integrating digital thermocouples and air sensors to refine ancient firing methods with precision data.

- Use refractory and heat-retaining materials that increase fuel efficiency and reduce thermal shock to the ware.

As sustainability becomes increasingly more pressing some potters are also exploring alternative fuels such as recycled wood, rice husks, and charcoal briquettes, reimagining kiln firing for the next generation in a sustainable way.

Japanese Kilns and Aesthetic Philosophy

More than mere equipment Japanese kilns embody the philosophy of wabi-sabi the belief that there lies beauty in imperfection and natural variation. A pot fired in an Anagama kissed by flame and ash is celebrated for its uniqueness as no two pieces ever emerge in the same way, making kiln firing a collaborative process with nature. This spiritual connection between artisan, fire, and earth is one of the many reasons why Japanese pottery remains deeply revered worldwide.

Final Thoughts

Whether it’s the primitive grace of an Anagama or the layered precision of a Noborigama, each kiln tells a story of patience and mastery.

As both an enduring legacy and an evolving craft, the Japanese kiln continues to fuel the creativity of ceramic artists worldwide and captivate collectors across the globe.

Share: