Soju, the iconic Korean spirit, has gained international popularity—but how does it fit into Japanese drinking culture? Do Japanese people drink soju? The short answer is: yes, but selectively. While soju is not a traditional part of Japanese alcohol culture, it is increasingly found in modern settings—from Korean restaurants in Tokyo to convenience store shelves. However, to truly understand its place in Japan, one must compare it with Japan’s native spirits: shochu and sake.

This article explores the complex relationship between soju and Japan—examining its similarities and differences with Japanese drinks, how it’s perceived, where it’s consumed, and what the future might hold.

Soju, Shochu, and Sake: Cultural and Historical Context

Soju and shochu share deep historical and etymological roots. Both likely originated from distillation techniques introduced to East Asia via the Silk Road and maritime trade, especially through Southeast Asia and the Ryukyu Islands.

Shared Origins and Etymology

Historically, the two spirits were often considered regional equivalents:

In Korea, shochu was known as "Japanese soju," and in Japan, soju was understood as "Korean shochu."

This overlap is not coincidental. In fact, the words soju (소주) and shochu (焼酎) are written with the same Chinese characters and mean the same thing: “burned liquor,” a reference to distillation.

However, over the past century, these spirits evolved in different cultural and regulatory ecosystems, giving rise to two distinct categories with unique production methods, ingredients, and cultural roles.

Ingredients and Fermentation: Koji vs. Nuruk

One of the fundamental differences lies in fermentation starters:

- Shochu and sake rely on koji mold, particularly white or yellow koji, to break down starches into sugars.

- Traditional soju uses nuruk, a Korean fermentation starter made from wheat and rice, which introduces different enzymes and native microbes.

This difference leads to distinct flavor profiles. Shochu tends to have earthy, umami notes, while traditional soju may be funkier and rustic. Mass-produced soju, however, often bypasses traditional fermentation altogether.

Production Methods: Artisanal Shochu vs. Mass-Market Soju

| Feature | Shochu (Japan) | Soju (Korea) |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Honkaku (single distillation) or Korui (multiple) | Distilled (often multiple times, then diluted) |

| Base Ingredients | Sweet potato, barley, rice | Tapioca, sweet potato, barley |

| Fermentation | Koji mold | Nuruk or ethanol base |

| Flavor Profile | Rich, earthy, grain-forward | Clean, sweet, neutral |

| Regulation | Strict domestic controls | Variable; more relaxed for diluted soju |

| Additives Allowed | Minimal (especially Honkaku) | Common in flavored soju |

Kyogetsu: A Korean-Style Soju Made for the Japanese Market

A unique case is Kyogetsu, a Korean-style soju brand that’s become popular in Japanese sunakku bars and hostess clubs. Packaged in larger 1.8L bottles, Kyogetsu is ideal for the “bottle-keep” culture where patrons store personal bottles at bars for repeat use.

Although made in Korea, Kyogetsu is marketed as “Korean shochu”—a localization strategy that helps it blend into Japan’s drinking norms while standing apart from native shochu.

Soju Consumption in Japan Today

While not mainstream, soju consumption in Japan is growing, particularly in urban areas influenced by Korean culture.

Where Do Japanese People Drink Soju?

- Korean Restaurants: Especially in areas like Shin-Okubo (Tokyo’s Korea Town).

- Convenience Stores: Jinro and flavored soju are increasingly stocked in 350ml bottles.

- Bars & Sunakku: Especially those with Korean clientele or K-pop influence.

- Home Drinking: Among younger Japanese who enjoy K-dramas and international trends.

However, shochu remains far more prevalent in households and traditional restaurants across Japan.

Legal and Tax Classifications: Why Shochu Has the Advantage

In Japan, shochu enjoys a special tax status that classifies it closer to beer than spirits, making it significantly cheaper than vodka or whiskey—and more affordable than imported soju.

Soju, as an imported liqueur or distilled spirit, is taxed at a higher rate and is not part of domestic subsidy programs. This limits its pricing competitiveness and reach, despite growing interest.

Rituals and Serving Styles: Soju vs. Shochu

| Aspect | Shochu (Japan) | Soju (Korea/Japan) |

|---|---|---|

| Serving Temp | Often with hot water or cold water | Typically chilled or on ice |

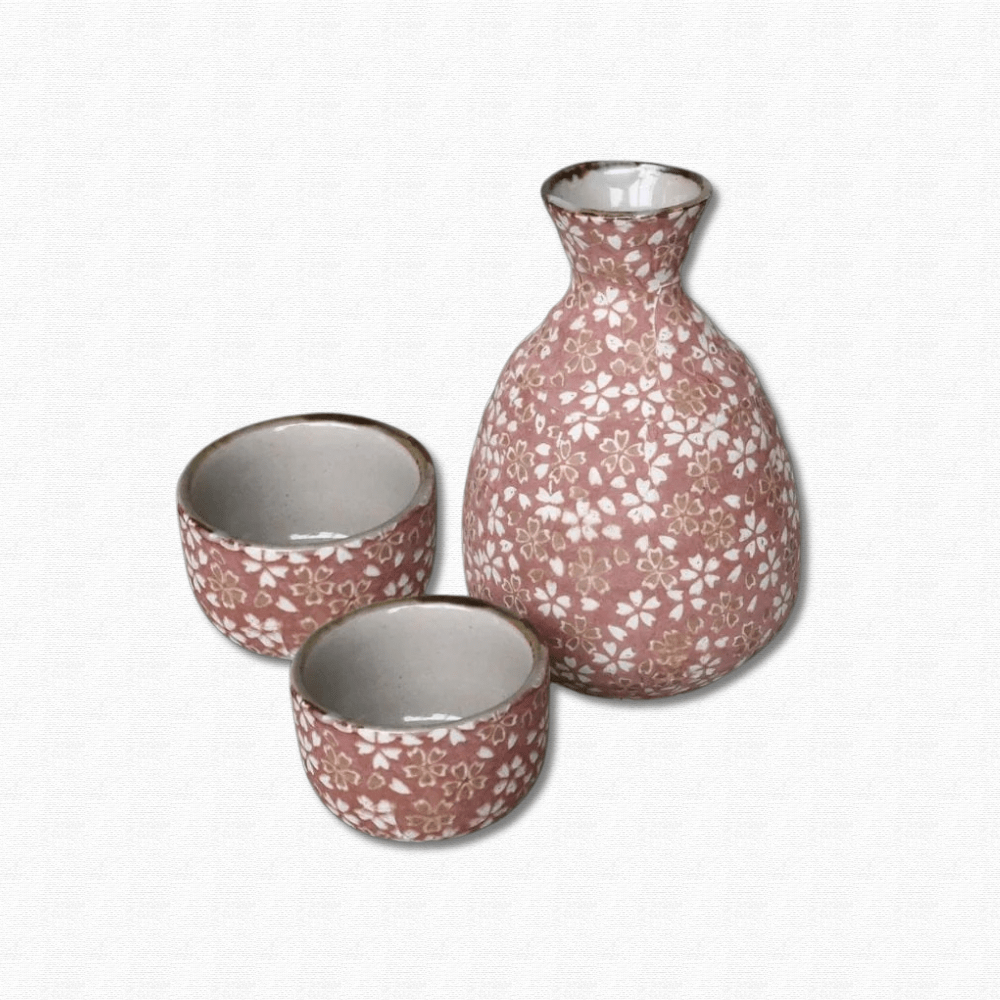

| Glassware | Ceramic cups, water glasses | Shot glasses, sometimes wine glasses |

| Drinking Style | Sipped slowly, often diluted | Consumed in shots or mixed |

| Social Rituals | “Bottle keep” at bars, family toasts | Pouring for others, group shots |

So, Do Japanese Drink Soju?

Yes, but within a limited and context-specific framework. Japanese drink soju:

- When dining at Korean restaurants

- As part of Korean pop culture experiences

- In bars that cater to Korean or international clientele

- Occasionally at home, especially flavored sojus

However, soju has not displaced shochu or sake, and is unlikely to in the near future due to tax barriers, production preferences, and cultural embeddedness of domestic spirits.

Future Outlook: Soju’s Niche May Grow

The growth of Korean Wave (Hallyu) culture, international tourism, and a general curiosity for global food and drink means that soju will likely continue growing in awareness among Japanese consumers—especially younger drinkers looking for something sweeter, lighter, or trendier.

However, shochu’s advantages in regulation, price, and tradition ensure its dominant place in Japan's alcohol ecosystem for the foreseeable future.

Share: