A Deep Dive into Japan’s Love Affair with the Bean

When people think of Japan’s beverage culture the tea ceremony (sadō or chanoyu) is the first thing that often comes to mind because of the centuries of history. But beyond matcha and sencha lies another beloved drink quietly thriving in the heart of Japanese daily life: coffee.

So that begs the question do Japanese people drink coffee? Absolutely! From historic kissaten to cutting-edge cafés, coffee has firmly rooted itself in both urban and rural spaces across Japan.

Coffee Consumption in Japan: A Daily Ritual

Coffee is not just enjoyed in Japan it’s a staple. As of recent global rankings, Japan consistently places among the top coffee-consuming nations with the per capita intake growing steadily over the last few decades. Coffee is enjoyed across demographics and settings:

- Canned coffee from vending machines serves as a quick fix during commutes.

- At-home coffee drinking is a comforting daily routine.

- Convenience stores (konbini) like 7-Eleven and Lawson offer surprisingly high-quality, freshly brewed coffee.

- Specialty coffee shops and cafés attract younger crowds and professionals seeking a more cozy experience.

Coffee is typically consumed in the morning or during afternoon breaks with morning service (breakfast sets served with coffee) being common at regional cafés like Komeda Coffee.

A Brief History: From Dutch Traders to Global Taste

Coffee first arrived in Japan in the 17th century via Dutch merchants in Nagasaki. However, it wasn’t until the Meiji era (late 1800s) that it gained a broader foothold. The real boom came right after World War II, as American influence and postwar modernization introduced coffee as a fashionable, international drink.

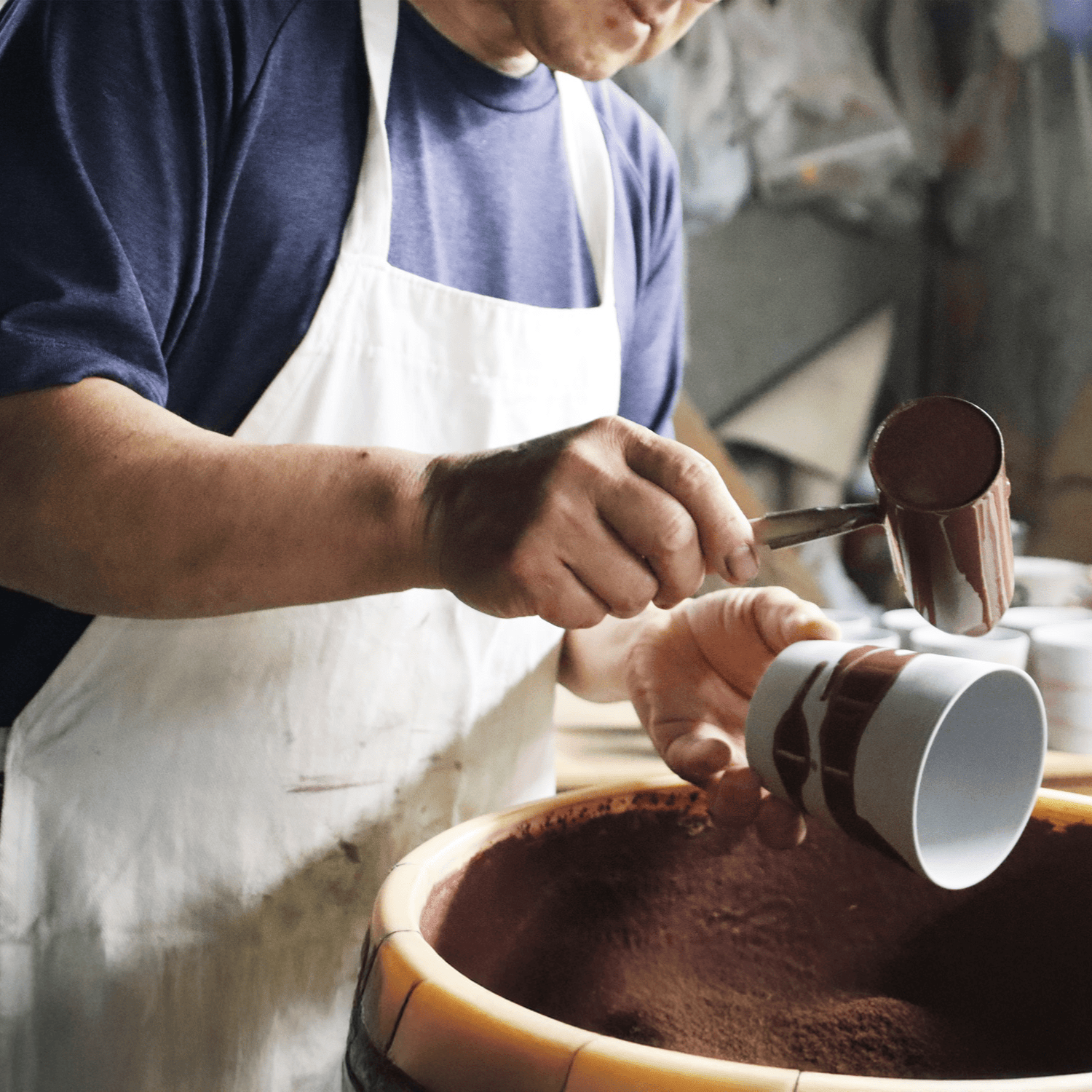

Pioneers like Tadao Ueshima, founder of Ueshima Coffee Company (UCC) played a pivotal role in popularizing canned coffee, a Japanese invention that revolutionized how coffee was consumed on the go. Over time Japan developed its own unique formats flannel-drip brewing, siphon coffee, and sumiyaki (charcoal-roasted) beans establishing a coffee culture rooted in tradition and innovation.

Coffee vs. Tea in Japan: A Harmonious Coexistence

While green tea remains deeply symbolic and essential to Japan’s cultural identity, coffee has carved out a complementary role as well. Many households now enjoy both tea and coffee with consumption often depending on the time of day or occasion.

- Green tea is typically associated with meals and wellness.

- Coffee is linked to work breaks, cafés, and personal indulgence.

Interestingly, Japan has developed hybrid experiences like matcha lattes and green tea-infused coffee drinks, blending the two worlds into one.

Coffee Shop Etiquette: Precision, Quiet, and Care

Similar to the tea ceremony, visiting a coffee shop in Japan comes with its own unspoken etiquette. Whether in a modern café or a traditional kissaten, the atmosphere tends to be quiet and contemplative. Here are a few things to take note of:

- Place your order politely by saying“Kōhī o hitotsu, onegai shimasu” (One coffee, please).

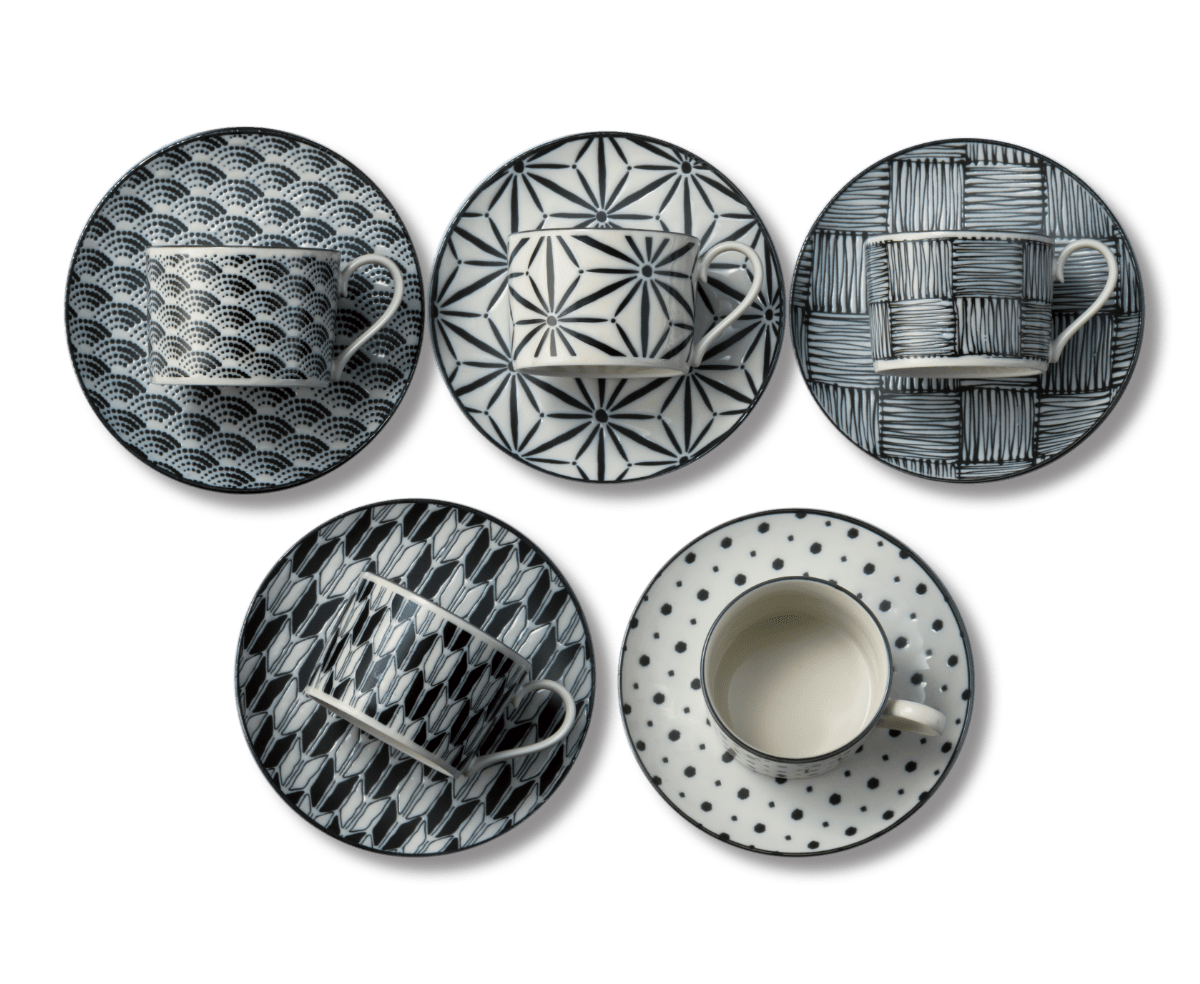

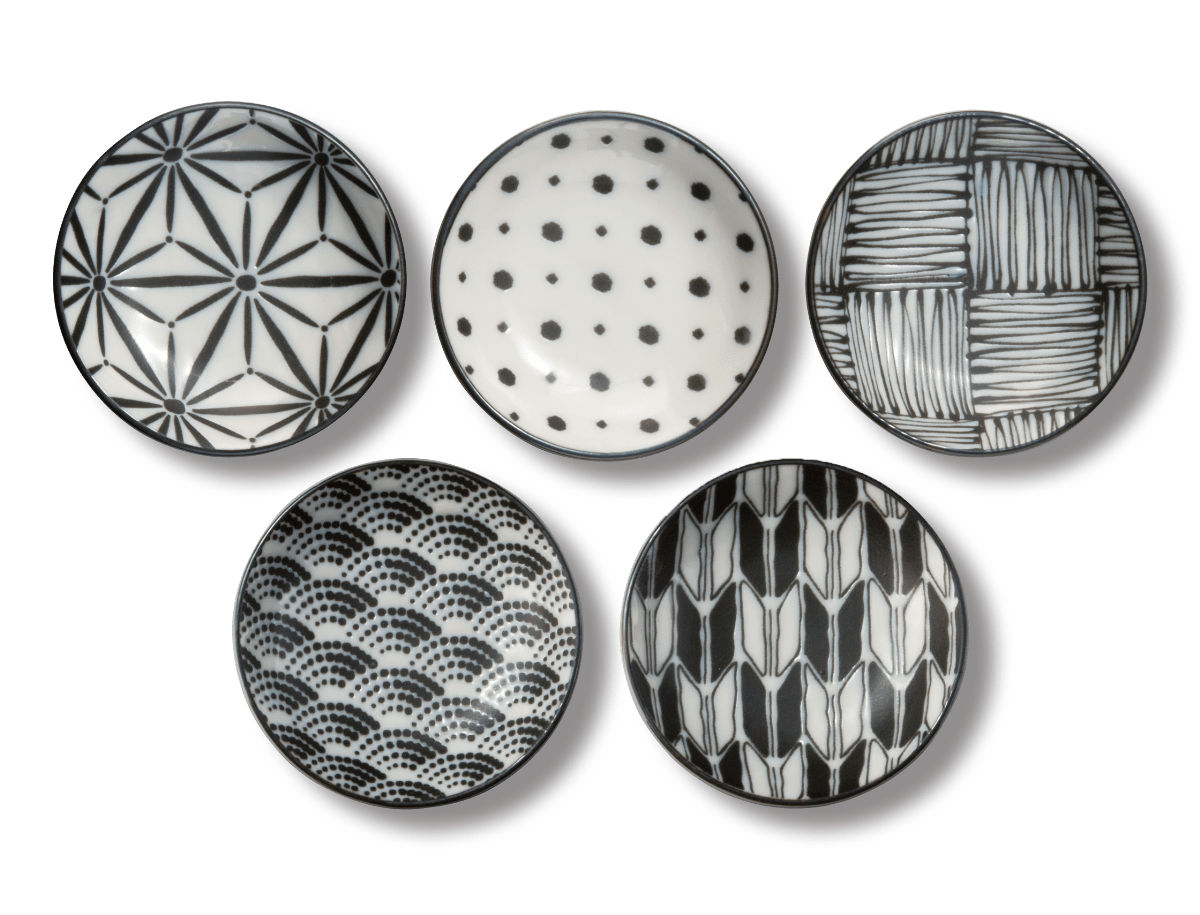

- Expect high attention to detail: baristas may serve your coffee on a small tray with a saucer, spoon, and napkin.

- Don’t rush. Drinking coffee is seen as a moment of pause, not speed.

Many Japanese cafés focus on latte art, seasonal menus, and precise brewing methods.

Modern Coffee Culture in Japan: A Blend of Old and New

Today, Japan’s coffee scene is as diverse as its regional cuisines. You’ll find:

- Specialty cafés like Koffee Mameya Kakeru or Onibus Coffee, known for single-origin beans and expert pour-over.

- Themed cafés, ranging from anime-inspired venues to zen-like spaces.

- Coffee vending machines in train stations and office buildings offering both hot and cold options on demand.

Major chains like Doutor, Tully’s Japan, and Starbucks also thrive often customizing their offerings to Japanese tastes with smaller sizes, local flavors, and more subdued interiors.

Regional and Seasonal Specialties

Japan’s regional diversity extends to its coffee:

- Hokkaido is known for rich, creamy coffee drinks perfect for its colder climate.

- Okinawa blends tropical flair with robust roasts.

- Kyoto and Kanazawa often pair coffee with traditional wagashi sweets in quiet, contemplative cafés.

Seasonal offerings like sakura lattes in spring or yuzu-spiced espresso in winter add a dynamic, ever-evolving character to Japan’s coffee landscape.

Traditional Coffee Houses: The Enduring Charm of Kissaten

The kissaten (喫茶店) is a uniquely Japanese institution. Popularized during the Showa era these classic coffee shops are often dimly lit, decorated with retro furniture, and serve hand-dripped coffee, toast sets, and homemade desserts.

Places like Chatei Hatou in Tokyo or Inoda Coffee in Kyoto have gained cult followings, known for their brewing and timeless ambiance. Visiting a kissaten is less about caffeine and more about atmosphere.

Bottom Note: Do Japanese People Drink Coffee?

Without a doubt. Coffee is deeply woven into Japan’s modern lifestyle, from morning routines and work breaks to weekend moments in artisanal cafés. While tea will always hold a special place in Japanese culture, coffee has secured its own place as well.

Share: